Super Bowl Monday Should Be A Holiday

From the Editor’s desk

Many of us are planning our festivities for this upcoming Sunday. Home chefs will start preparing countless dips on Saturday. The fryers at wing joints will be at a boil from dawn until the start of the game. Fantasy die-hards are putting together rosters for niche leagues designed for those folks not content with the standard regular season. People are preparing their homes to host friends and family to take part in a truly global event, one that their game tickets, team attire, TV subscriptions, and tax dollars have paid for. And, just as sure as they will watch, most Americans will get up early on Monday to return to work. They will step out into a cold, gray world, one entirely devoid of the spectacle of the previous night. They will be short on sleep. They will be unproductive. They will be, in a word, miserable. But they don’t need to be. We can decide as a society to give ourselves a break, and we should. We should make Super Bowl Monday a holiday.

The Super Bowl remains one of the few near-universals in American public life and should be treated as such. Because of the vast number of streaming services, YouTube channels, social media apps, and other diversions, consumers often find themselves on islands, isolated from other consumers. The most popular streaming show this week, HBOMax’s The Last of Us, drew 4.7 million viewers (Guy), which is about 1.4% of the population. If you’re on a bus with 50 people, you might not have anyone with whom to discuss the episode. Gone are the days of M*A*S*H, when 106 million people (Andrews) would tune in for a single episode of a show. We have become more atomized as a society, and the Super Bowl is one of our few remaining mass media events. It’s something we can all stop and talk about; such events are a critical–not to mention vanishing–part of a functioning society. According to the NFL and Neilson, more than 208 million people watched Super Bowl LVI. Compare this with the 2020 election, in which 158.4 million voters cast ballots (DeSilver). Nor were these numbers unusual for a Super Bowl; according to Dr. Jeffrey James–a sport management professor at Florida State University–9 of the top 10 broadcasts of all time have been Super Bowls (Kroeger). Just as the Romans have a cultural legacy associated with gladiators, chariots, and bread & circuses, the Super Bowl will forever be part of the American cultural legacy. To say that it is just another game and should be treated as such is simply wrong. And it doesn’t end when the last second ticks off the playclock. After the actual Super Bowl is over, you watch the presentation of the trophy, the naming of the MVP, and the postgame analysis. You watch interviews with the coaches and players. Should you end these festivities so that you can be bright-eyed and bushy-tailed for work or school? Would the Romans have stopped handing out their post-chariot race laurel wreaths so everyone could show up early the next day to repair aqueducts? I should think not. Nor should we.

We should not let everyone’s most hated Monday interfere with everyone’s most beloved Sunday. While there are some people who may actually be productive on the Monday after the Super Bowl, the vast majority of Americans will not be up at dawn drafting memos or holding important meetings. In fact, more than 17 million people are likely to avoid work on Monday, February 14th, leading to a “productivity loss [that] could top $4 billion” (McGregor). How little actually gets done on Super Bowl Monday? Well, according to the Washington Post, 72 percent of HR managers think that Super Bowl Monday should be a holiday. And what can the captains of industry do to boost productivity on these days? Not a whole lot, it turns out. According to a Kronos study, 62% of executives just laugh it off because, well, there’s nothing else one can do. They have taken the view that one must simply accept that not a lot will get done on Super Bowl Monday, and that is perfectly fine. To take it a step further, rather than pretending that we will show up early and conduct our business affairs with our usual zeal (and chuckle at those rogues who call out with Eagles fever), maybe it would be better to simply tell everyone to show up bright and early on Tuesday, ready to retake our places at our grindstones. But a day off isn’t just good for the bottom line; it is also good for mental health.

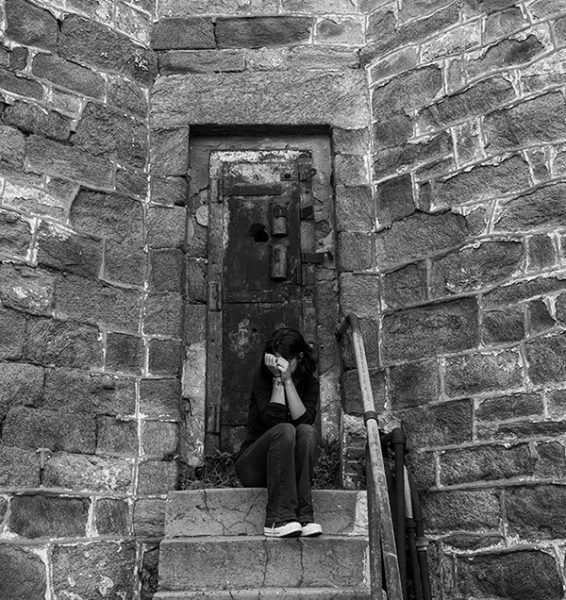

Mid-winter is a difficult time of year for people and adding an extra holiday is an easy way to bring cheer during the gloomier months. Roughly 25 million Americans report feeling the winter blues, and an additional 14 million have actual diagnosed seasonal depression (Rogers). According to BYU’s Marriott School of Business, people who suffer from the winter blues should “get a good night’s rest and to get out of the house and be social” (Rogers). The Super Bowl parties certainly provide the latter two, but they seriously undercut the former. The last time the Eagles were in the Super Bowl, I managed to get 5 hours and 41 minutes of sleep, certainly well below the marker for what qualifies as healthy sleep. On a Friday, this amount of sleep is manageable; on a Monday morning, this presages a long and unhappy week.

But the Super Bowl has always been on a Sunday (some sticks-in-the-mud will say), and things have always worked out, so why change it now? This is the suck-it-up-buttercup argument, and it stinks. Just because others were miserable, so too should you be miserable. If we want to play the history and tradition game, though, I am fine with it; let’s play that game. Winter celebrations, such as those the celebrate the solstice, are as old as humanity itself, are generally longer than our current handful of days off, and are important parts of all human societies. Here are just a few examples spanning the entire globe. Hawaiian winter festivals required that “all manual labor [be] prohibited [for]…several whole days of resting and feasting” . In Pakistan, the Hunza people “occupied themselves playing music, telling tales, drinking wine and dancing.” Yalda night celebrations in Iran saw “family and friends [staying] up all night, [telling] stories and [eating] watermelons” (“Winter Solstice Celebrations Around the World”). Wherever the days are short, you will find people taking time off from work and other responsibilities to feast and enjoy games; why not make a long Super Bowl weekend part of an extended American mid-winter tradition? It seems to have worked everywhere else for about as long as humans have existed; it seems like its worth a try here.

While we may no longer all take part in a physical harvest, our sports are part of the economic harvest that we should collectively enjoy. US consumers and taxpayers invest heavily in sports, whether they know it or not. The US federal government has subsized stadiums “to the tune of $3.2 billion federal taxpayer dollars since 2000” (Gold). Unsurprisingly, the much-touted economic benefits of a new stadium over an old stadium are wildly exaggerated: “the inescapable truth is that the economic impact of these projects on their communities is minimal, while they can be an obstacle to real development in local neighborhoods” (Gold). Taxpayers are harming the communities they live in by throwing tax money at billionaires who will threaten to move these beloved teams to new cities if funds intended for firehouses and schools and libraries are not directed to new practice facilities. In some respects, you’ve already paid for the game, so why not actually enjoy it?

But what if you don’t watch football and aren’t close enough to any professional teams to worry about the economic effects of new stadiums? If you are reading this in NJ and are considering going to school (or have already attended school) in state, you are affected by this. For example, Rutgers University–which has two players in this year’s Super Bowl–is part of a well-funded feeder league currently attached remora-like to the body of our higher education system. While I enjoy seeing players from my alma mater in the big game, I am horrified that “Rutgers athletics has been running yearly operating deficits of between $23 million and $73 million” (O’Neill). The Scarlet Knights have lost a quarter of a billion dollars building a football program, and they have been doing it with tuition and tax dollars. Once again, you have–in many regards–already paid for the game, so the least society can do is let you enjoy the whole thing.

The morning commute the day after the Super Bowl is a solemn affair, but it is one that we, as a society, can largely do away with. Building a better work-life balance as a society is never easy, but this is one small step that we can take together. I hope to see you all out one Monday, hopefully not too far in the future, for a post-Super Bowl brunch.

Go Birds.

Chase • Feb 8, 2023 at 10:24 am

I think that having Super Bowl Monday off is a great idea because even if your team isn’t in the super bowl, most people end up watching anyways. When your favorite team ends up winning the Super Bowl people generally stay up even later causing everyone to be sluggish and tired the following day, besides if not many people show up than what is the point of having school or work that day.

Nina Ferrari • Feb 8, 2023 at 10:24 am

This article completely and thoroughly lays out the reasons as to why the Super Bowl should be a holiday. This should be taken into serious consideration and allow the U.S to have Monday off because of the importance of this event.

James • Feb 8, 2023 at 10:21 am

I agree